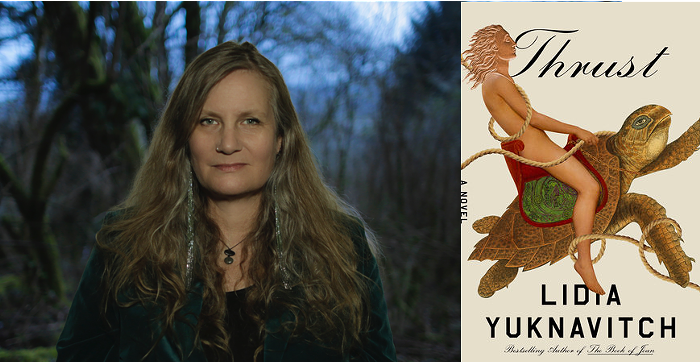

If anyone has been instrumental in keeping literary Portland weird, it’s Lidia Yuknavitch. From her bestselling books to her much-written-about writer’s group with local literary darlings Cheryl Strayed, Chuck Palahniuk, and Chelsea Cain, to her quirky, indescribable writing center in the Postal Building downtown, Yuknavitch has emerged as a literary force in this city: radical, inclusive, anti-establishment, and just really fucking weird. She's a writer for misfits in a city of misfits.

Which isn’t to say that Yuknavitch’s talent hasn’t touched readers on a national scale. Her TedTalk on the beauty of feeling like you don’t belong has been viewed over four million times, she is the recipient of two Oregon Book Awards, and her cult memoir, the Chronology of Water, is being adapted to film by Kristin Stewart.

Yuknavitch’s newest novel, Thrust (Riverhead Books), is a nonlinear traverse across time and history that casts a bracing eye on the myth of America. Already named a best book of the summer by a handful of publications, Yuknavitch's new work has received gushing reviews: the Washington Post called it “the weirdest, most mind-blowing book about America,” the LA Times named it “ a blistering excoriation of power structures."

The Mercury spoke with Yuknavitch, preceding Thrust's Tuesday June 28 release, about the role of climate crisis in storytelling and how the pandemic changed the Portland literary scene.

PORTLAND MERCURY: Why do you think your new book is striking such a chord right now?

LIDIA YUKNAVITCH: If it is striking a chord, the chord is dissonance—a kind of storytelling askew, which seemed to me the only way to rearrange the stories being heaped upon us all over the world. Anyone, any artist diving into the waters of expression right now will encounter a kind of impossible set of truth: binary ideas in a knot with each other, hope and fear and brutality and beauty all wrestling for air. I am trying to bring those dissonances to form. I am trying to imagine that we still carry story and song in us, but we have to listen differently.

There is a climate change current in Thrust. How can we use fiction to change the stories we tell ourselves about the climate and our future as a species?

That is the primary beauty of storytelling (one of our oldest expressive forms). Any story that can be expressed can be de-storied and re-storied. That has a danger in it, but it is also always a profound possibility-space. So when I think of how to change the story, I think of a polyphonic chorus made from scientists, artists, activists, historians, philosophers, or just people at the edges of things, daring to still dream. For me, storytelling is one form of resistance and resilience in the face of chaos.

The Pacific Northwest is obviously grappling with the impacts of climate change—devastating wildfires, fatal heat, summers filled with smoke, ice storms, flooding—did that impact the writing of Thrust?

Mightily. Although, in my lifetime, climate change has been threaded through every moment of my existence—before I was born, and likely after I die. So the moment may seem like it erupted in our present tense, but that is not the case. Our slice of existence seems urgent to us because we are alive right this second, but linear time is a human construct we use to help us navigate our years. So absolutely climate change is at the heart of Thrust—global climate change. Cosmic epochs. Not just Portland.

A thread among all of the reviews of Thrust—and a common reaction to your work in general—is the acknowledgement of your wild, unbound voice and stories. What practices / rituals / beliefs help you nurture that ability to just be really fucking creative without holding back?

For me, water / immersion / swimming is akin to traveling the vast realm of the imagination. So putting my body in water—or in relation to water—has creative and symbolic resonance for me. I've made a practice of making art, I've made a practice of immersing myself in the art of others, I've made a practice of helping others find their own expressive forms.

And I ritualize like a motherfucker. With rocks. With walks. With talking to trees. With drawing and painting. With other art by other people. With my own dreams. With food. With people.

Your writing center, Corporeal Writing, has served for years as a literary hub for the Portland writing community. How did the pandemic impact it? Are you still downtown?

Oh man, like legions of others around the globe, our micro arts organization experienced plate tectonics for sure. We nearly went under several times, but instead of dwelling on the catastrophic, we asked questions of ourselves about adaptation and evolution, and that helped! We morphed.

Corporeal Writing is still alive—not because of me, but because of the love and labor of our team (Domi Shoemaker, Daniel Elder, Katie Guinn, and Anya Pearson) as well as all the humans who took turns keeping us afloat. Thanks to everyone taking turns shoveling shit or plugging the holes or helping each other to NOT DROWN, we're thriving. We're growing and changing.

How do you see the Portland literary community as a whole bouncing back from these 2+ years of isolation and separateness?

I feel a lot of sadness and grief and loneliness when I'm in a room with others just now. I'm not surprised. The world has collectively gone through gigantic traumas—all in a row and ongoing—but we haven't had a chance to experience our grief and loss and begin to heal. I think that with one breath at a time, one person holding another person's hand, we have a chance to take turns resuscitating each other.

I'm all in.

Lidia Yuknavitch will be joined in conversation with Vanessa Veselka at Powell’s City of Books, 1005 W Burnside, Tues June 28 at 7 pm, FREE