Even on their most accomplished days, Multnomah County COVID-19 tracers only contacted 80 percent of people who reported positive tests during the pandemic, according to a report by the Multnomah County Auditor’s Office released Wednesday. Amid the pandemic’s largest surges, only 10 percent of people who reported positive tests were contacted by tracers.

While state guidelines directed county tracers to contact every person who tested positive for COVID, the audit notes that contact tracing—the process of calling and interviewing all COVID-positive people to gather information about who else they may have infected—was ultimately not realistic or possibly even appropriate during surges in cases throughout pandemic. However, the audit concludes that the Multnomah County Public Health Department can learn from the tracing team’s challenges to better prepare for future emergencies.

“We encountered myriad unknowns as we stood up a response to this brand new, potentially deadly virus that quickly became one of the most contagious infections ever known,” said Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury in a written response to the audit. “And since the COVID-19 pandemic is not over, our interventions continue to be responsive to the growing needs of our community, with specific care for our marginalized populations.”

COVID contact tracing became a state requirement in May 2020 when Governor Kate Brown made having a contact tracing team necessary for individual counties to “reopen,” or rollback early pandemic restrictions like physical distancing and nonessential business closures. Brown required each county to have 15 COVID tracers per 100,000 residents, which equated to 122 tracers in Multnomah County. As of early June 2020, Multnomah County pulled together a team of 63 tracers with the goal of reaching 122 by the end of the month. In reality, the team never reached its target, peaking at just under 100 tracers in October 2020.

According to the audit, the number of COVID cases reported in the county “frequently exceeded” Multnomah County Public Health’s tracing team’s capacity to conduct universal case investigations. During the pandemic’s surge in fall 2020, investigators were able to interview approximately half of the people who reported COVID cases. In summer 2021, when the delta variant rocketed the pandemic to new records, investigators called 20 percent of people with reported cases. Then, when the omicron surge outpaced all of the previous pandemic case loads in late 2021, tracers only interviewed 10 percent of people who reported a positive test.

Of the 70,000 reported COVID cases in Multnomah County from early March 2020 to January 2022, the audit found that contact tracers called 30,000 of them. The report identifies staffing, budget planning, and overall pandemic conditions as limitations of the contact tracing team.

While overall pandemic conditions strained everyone’s staffing levels, interviews with county employees revealed that limited human resource training on things like workplace culture, union stipulations, and overall expectations slowed down the onboarding process. Employees told the auditors that establishing ready-made onboarding materials for quick hires during an emergency would be beneficial.

Planning for future needs proved difficult for the public health department during the pandemic as well. Believing that the availability of vaccines and more easily accessible testing would slow COVID cases, Multnomah County health officials requested a smaller budget for the contact tracing team for the 2021-2022 fiscal year. When the delta and omicron surges obliterated previous pandemic highs, the county didn’t have the budget to expand its team of investigators. However, it’s unclear if a larger team would have produced better tracing outcomes.

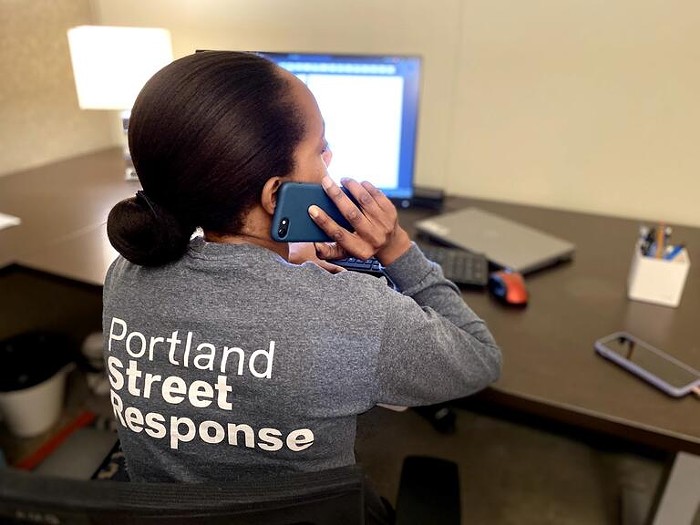

As COVID variants became more contagious and fast spreading, the effectiveness of contact tracing during the pandemic diminished nationwide. Contact tracing requires people to call COVID-positive residents, interview them about where they were, who they were in contact with, and advise them on how to quarantine. It’s a laborious task with the goal of making sure anyone who may have been infected by the COVID-positive person quarantines in case they also were infected, thus limiting the spread of the virus. However, as each variant became more transmissible and symptoms didn’t appear until after someone’s most contagious phase of infection, contact tracers were unable to keep up.

By January 2022, county health officials knew that COVID spread was far outpacing tracing efforts and decided to end individual tracing in favor of tracking large outbreaks, like a cluster of cases at a group care facility or school. One month later, the CDC stopped recommending contact tracing for COVID completely.

While contact tracing became a less effective tool to combat the spread of COVID, the report asserts that county tracers not calling 40,000 COVID-positive residents represents another problem. Residents were connected with the county’s COVID wrap-around services—like programs that helped people exposed to or infected with COVID get grocery deliveries or rental assistance—through those phone calls with contact tracers. While someone could technically reach out for grocery and rental assistance on their own behalf, the audit found that the resources were not widely advertised to the public.

Because the pandemic clearly demonstrated the limits of contact tracing, the audit focuses its recommendations on broader structure and process concerns that could apply to future emergency responses.

The audit makes seven recommendations for improvement, such as establishing a process for redeploying county workers to more high-demand programs during an emergency and providing education to community organizations that collaborate with the county during emergencies on the county’s reporting requirements and expectations. All of the recommendations must be completed no later than July 1, 2023, with some recommendations needing to be completed later this year.

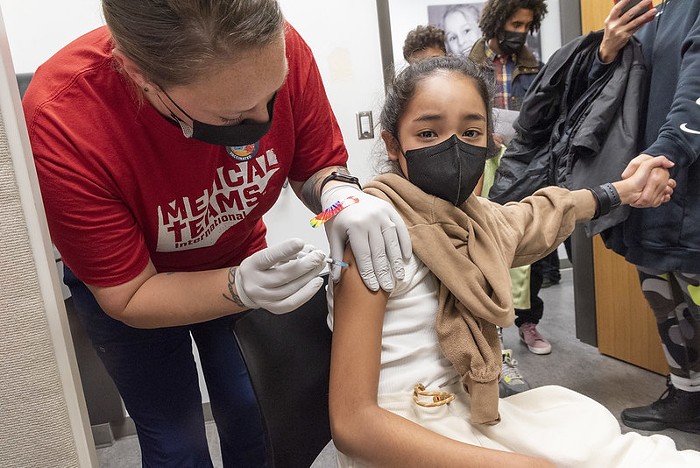

In a written response to the audit, county chair Kafoury agreed with all of the recommendations and indicated that the county has already started on the recommendation to provide education on county processes to partners, like community-specific nonprofits who hosted vaccine events or provided other COVID-related resources. Throughout the pandemic, county health officials praised the collaboration that occurred in response to the emergency, but also stressed the need to maintain and solidify those partnerships to build a stronger health system overall. According to Kafoury, the county is hosting outreach events to train potential partners on how to use the county’s internal systems and developing a process to ensure community partners’ fiscal compliance with county and federal funding.

The Multnomah County Public Health Department is also conducting a full “After Action Review”—an in-depth report following a major response to a problem—that will further detail how pandemic-related struggles can be used to inform improvements in the county health system.