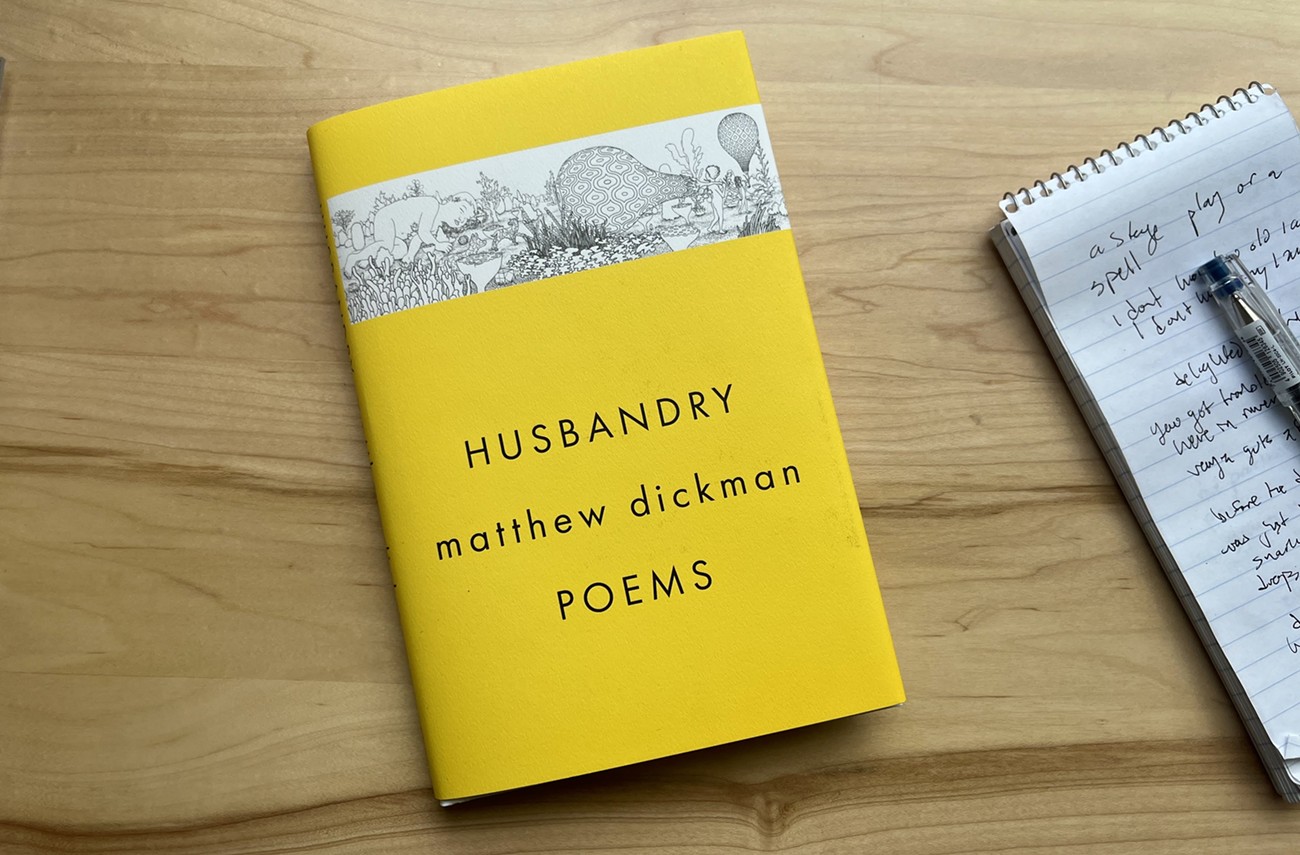

When Matthew Dickman answers the phone he’s in the middle of folding laundry, an act we see much of in his new collection Husbandry (Norton, 144 pages). Midway through, there's even a poem called "Laundry," which reads: "And when I would rise / to put everyone's clothes / away I could hear / a lost bell / inside me ringing / each article of clothing / an accounting / of devotion." Three couplets later the poem reveals his partner has been "in the dark / with another person / removing clothes / I had just folded."

"Laundry" is a good example of the trajectory Dickman's fourth poetry collection takes, as it explores devoted domesticity and a painful breakup that precipitated his newfound world of single parenthood. One could take the dissolution of Dickman's longtime relationship with a bitter eye, but Husbandry seems to merely present it for context, the way that any Dickman poem will assemble a haunting diorama of specific, heart-piercing references, like a long equation he's trying to solve.

"I write poems about things I want to figure out," he told the Mercury. "I would never write a poem about a completed story or something I knew as an integral truth to myself—because what's the point?"

Dickman's poems have always been about personal subjects. His 2012 Mayakofsky's Revolver centered on the suicides of people that were close to him and the 2018 Wonderland described a childhood of watching friends become neo-Nazis in Portland's Lents neighborhood. But a lot of the pleasure to be found in his work comes through at the most mundane moments—in Husbandry it's the repetitive act of folding clothes. In one of Wonderland's poems, "Minimum Wage," which graced the pages of the New Yorker, it's smoking with his mother on the front porch.

Husbandry is Dickman's most focused work to date, an entire collection centering around parenthood, wherein Dickman—who grew up without a father—traces a nurturer-Saturn trajectory of recognizing himself in his children and making difficult choices about how to handle that.

The collection's first poem "Goblin" addresses these Saturn and child situations: "the children are supposed / to die. In some stories / they do. In others they / survive but must kill." In the poem, Dickman is playfully chasing his youngest when the situation takes a sinister turn. "And I know / I shouldn't have / really become a goblin," it reads. But when his son begins to cry, Dickman is quick to stop and hold him.

"I realized that through fathering and through being a father," Dickman explains, "in a weird way, I was able to parent myself and to kind of father myself."

Husbandry unfolds in couplets, but the form doesn't negate Dickman's congenial tone. While the breaks feel intentional—I mean, couplets—if you've heard him read, you know that Dickman orates his poems conversationally and often like he's telling you a story he really oughtn't. He knows how to end a line on something scintillating, like someone telling you really good gossip before they step into another room.

"I'll tell you my biggest fear," Dickman says, regarding his reading style. "My biggest fear is that someone will finally figure out that these books—Husbandry, Wonderland, and Mayakofsky's Revolver—are just Dickman talking. And people will be like: 'That's not art. That's just this guy, like, talking out loud.'"

However, something that doesn't bother Dickman is the idea that someone might pick up Husbandry just to read all about his love life. Both Dickman and his publisher cleared more personal aspects of the collection with his former partner, and it's not surprising that a person Dickman spent many years with would also—as they told the Mercury—"believe in an artist's right to express their own subjective truths."

There are some juicy, sad bits in Husbandry, but the heartbreak is exposed in an accessible way that feels highly relatable, and gives off the impression that the collection could cross over from devoted poetry detanglers to a more general readership.

"I've always just tried to write poems that I would like, if I picked it up and didn't know the poet," Dickman says. "I do tend to write in a way where someone who may have been mis-taught poetry in high school—I think they could pick up one of my poems and feel something."

Matthew Dickman appears tonight in conversation with Chelsea Bieker at Powells City of Books, 1005 W Burnside, Wed July 13, 7 pm, FREE