When Metro President Lynn Peterson was in school for civil engineering, she was taught how to design roads to get a vehicle from Point A to Point B in the most efficient way. Through her career at the Washington State Transportation Department, TriMet, and now leader of the Portland metro area’s regional government, Peterson found that her training didn’t address the more complex realities of transportation engineering—like how the transportation system can impact quality of life metrics or how investments in new transportation infrastructure could enable gentrification without the proper safeguards in place.

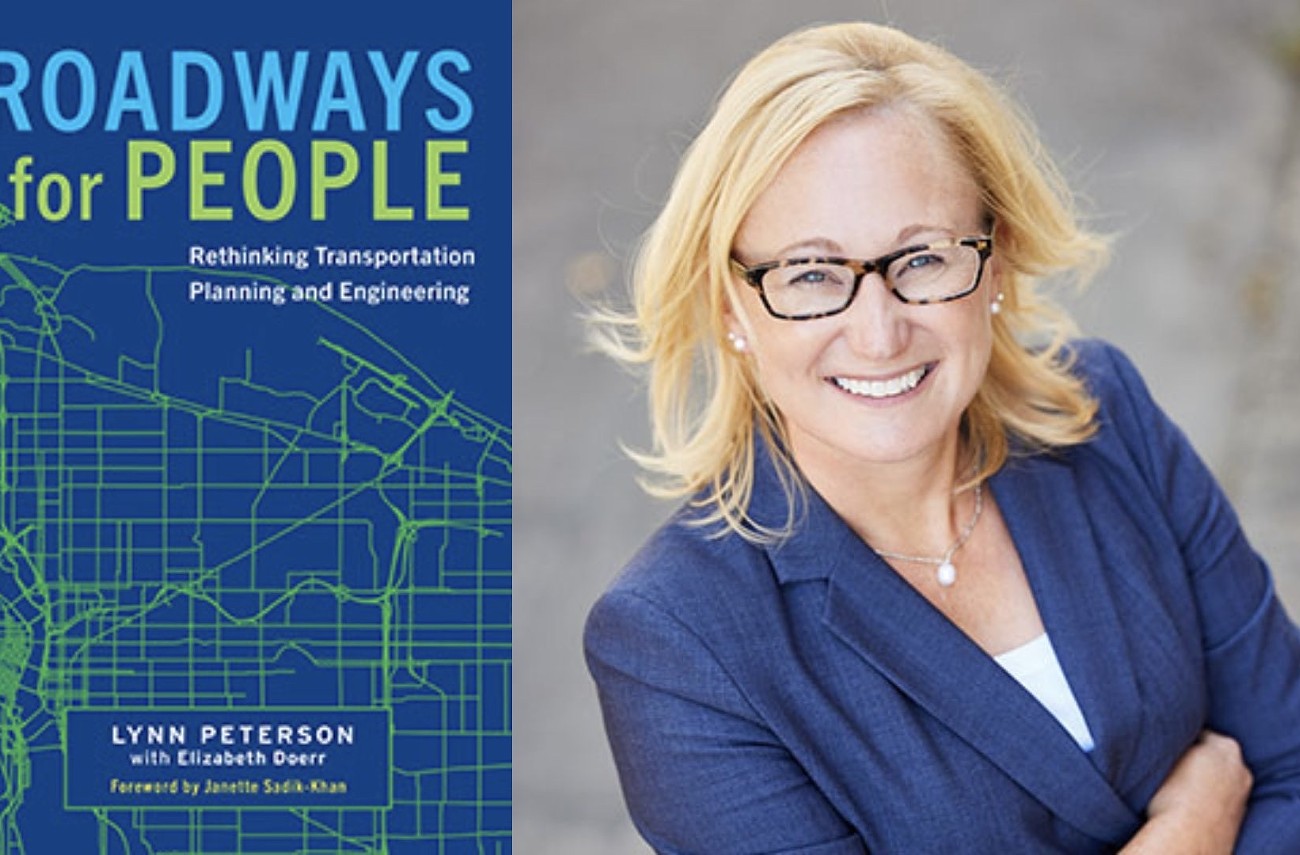

Peterson, with the help of writer Elizabeth Doerr, addresses those complexities in Roadways for People: Rethinking Transportation Planning and Engineering, published in early December by Island Press. The thesis of the book is straight-forward: Transportation engineers must engage community members when deciding how to address a problem within that community, not dictate a solution to them based on limited data. In other words, transportation engineers should not do what the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) did when starting the Rose Quarter Interstate 5 project, which Peterson and Doerr use as an example of an outdated transportation project planning process.

In 2017, ODOT developed a plan to address bottleneck congestion in the Rose Quarter region of the I-5 corridor by adding additional ramp-to-ramp connection lanes. Peterson notes that ODOT followed the typical public engagement process when developing the plan—a process that enables transportation agencies to treat public engagement as a task to check off a list as opposed to a meaningful conversation that can provide critical insight.

“While ODOT was required to hold community meetings, the information gathered from those public meetings with local entities and thought leaders was not used to understand the nature of the challenges the people in the community experienced along the corridor,” Peterson wrote. “As a result, the department narrowly defined the problem: congestion on the interstate between three closely spaced urban exchanges.”

While congestion in the Rose Quarter section of I-5 was—and still is—a problem, ODOT failed to see the larger problem raised by the surrounding community in the following years: the original construction of the freeway corridor decimated Black-owned homes, cut off economic growth in a historically Black neighborhood, and polluted the air around a school. Through years of community advocacy and intervention from powerful political leaders, ODOT has adjusted the project to address more of the community’s concerns, but it has led to delays in the project timeline and ballooning construction costs.

Peterson argues that ODOT may have been more successful from the beginning of the Rose Quarter project if it had started with what Peterson and Doerr call a “community solutions-based approach”—a process-oriented approach that requires the project-area community to help define the problem and give feedback on the solution. The approach, Peterson argues, is critical to developing projects that properly address a community’s specific transportation—and sometimes non-transportation—needs while also receiving community buy-in on the project.

The Mercury talked with Peterson and Doerr about the community solutions-based approach and how it can be applied to ongoing transportation projects in the Portland region.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERCURY: In the past couple years, Portland transportation leaders and experts have talked about the importance of the same values you lay out in the community solutions-based approach. Can you characterize how prevalent this approach is on a national level?

PETERSON: City department of transportation (DOT) folks have certainly been on this page for the last two decades, or longer. The state DOT doesn't have the same urban perspective [as city DOTs]. The state has very rural standards and basically wants no development along its roadways because that means more trips, more demand, more unsafe conditions, and it gets too complex for how they want to manage the system, which is a lot of traffic going fast.

If you can imagine trying to create an entire interstate system where you have thousands of engineers engineering, you want to set those engineering standards as narrow as you possibly can so that you can uniformly meet driver expectations, and you don't have to have as much oversight if you just assume everybody is copying the standards exactly. That's where this older thought process, that there is no flexibility, comes from—but there's actually a lot of flexibility to include community values as part of the performance metrics and get the outcomes they want. [For example], including construction apprentice jobs in projects, or affordable housing that you either need to protect or build in a corridor.

DOERR: There are a lot of national advocacy organizations that are taking an equity approach, like Smart Growth America and Transportation for America. I also talked to Dara Baldwin from the Center for Disability Rights [for the book] as well. There are a lot of national advocacy organizations doing a lot to change the discussion and to make sure that the engineers and the planners who are doing this work are understanding the past harms that this industry has done to communities and to keep those in mind.

PETERSON: There has been a cadre of states who have had progressive state DOT directors using these values. Washington, Utah, Colorado, Minnesota, and even some of the southern states—ones that have been hard pressed for money—end up getting more innovative around these things. It's a spattering of states across the United States that are really trying to figure it out, but Oregon has been a little bit behind.

The first chapter focuses on the I-5 Rose Quarter project led by the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), particularly as an example of what not to do. When that project first began, ODOT did not engage the community properly which has led to an ongoing deficit of trust. In the book, you characterize the project as a “roller coaster” before writing, “I feel that ultimately [the Rose Quarter project] will go in the right direction.” What gives you confidence in the project?

PETERSON: The Rose Quarter project started before ODOT Director Kris Strickler came on board, and he, having worked both as a co-lead for the Columbia River Crossing project [the failed attempted to replace the Interstate 5 bridge] and working at the Washington Department of Transportation, has much more understanding of what it takes at the community level. [Under his leadership] best practices are slowly being absorbed into ODOT after about two decades of zero money for training on best practices from the Oregon Legislature. I think ODOT has been in a little bit of an isolated bubble, and not participating in national conversations. [ODOT’s lack of public engagement at the beginning of the Rose Quarter project shows] there is no such thing as a shortcut. You can't come in and have a project defined with a cost estimate and have never talked to anybody about it. That's a shortcut to disaster.

You think Strickler instills community engagement as a value at ODOT?

PETERSON: Yes. Every time, without exception, an issue has arisen because the Rose Quarter project started with a shortcut, because there's all these ramifications of doing that. Every single time an issue comes up, Kris Strickler is like ‘Okay, hold on, slow down. We're gonna have to pause to negotiate this, because we did not start this conversation right.’ [When staff is worried about timelines and budget], it takes courage to say no, we gotta get this right.

Let’s talk about how the community solutions-based approach can be applied to the Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR). When you have so many government partners in a project, all representing communities who may have competing needs, how do you maintain the integrity of a community solutions-based approach?

PETERSON: I’ve probably said it one thousand times: there is no perfect. ‘Perfect’ is completely different from everybody’s perspective. What we lay out in the book is that there is no linear approach to this—you have to be willing to be inclusive and understand what's driving somebody's request. Addressing the underlying barriers [that prevent community engagement is following a community solutions-based approach]. Maybe we haven't created safe environments for people to even give us that information. If someone can’t leave work or can’t do unpaid work, what are we doing to cover their costs [so they can participate in community engagement]? We can get daycare. We can make sure the conversation is in plain language so that they can participate. We can make sure that those who are asking the questions are reflective of the actual community and speak the languages that they speak and then can interpret any of the cultural differences.

What the IBR project has done well is acknowledging that there are a lot of people who would be impacted by [the bridge replacement] now and in the future and that those voices should be heard. Those voices were previously ignored [in the Columbia River Crossing project, and ODOT’s previous process] because it was a transportation project, and therefore only transportation experts should be involved. The process excluded everybody except who they could create an echo chamber of interests with.

DOERR: In the book, we use two examples of the community solutions-based approach that are completely different from one another because we wanted to focus on the fact that it's a process. It's not going to be necessarily a pretty process, it’s not going to be super straightforward, but what Lynn is getting at is when projects are now being critiqued, it's probably because they started out the wrong way. One of the big takeaways we want people to know is that these conversations should include as many coalitions and people and community members as possible. There are going to be some hard conversations, but if they're facilitated well, you are going to create more buy-in from the community.

Do you think there is movement towards this type of community engagement and planning in transportation projects nationally?

PETERSON: Looking nationally, there is a trend line toward doing this. What I wanted to take advantage of [in the timing of this book] is that more and more people are interested in this, and more people need to have the conversation of what success looks like. How do you set the table for a more inclusive conversation and how do you value lived experience? We haven’t been having those discussions because we’re afraid, and we don’t need to be afraid. There is so much instilled in transportation engineers and planners’ minds about the risk of talking to the community—they believe it’s a risk to the project to talk to community [because it might cause delays or extra costs] and what we’re saying is, it’s a risk to not talk to community.