Portland homeless shelter providers were taken by surprise in October when Mayor Ted Wheeler and City Commissioner Dan Ryan unveiled a plan to open several large-scale outdoor homeless encampments across town. Many longtime organizations, several of which already ran outdoor shelters similar to the proposed camps, had expected the city to seek their input in the proposal.

“But no local provider had been consulted,” recalled Andy Miller, director of homeless service nonprofit Our Just Future (formerly Human Solutions). “That just felt strange.”

Instead, email records show a California-based nonprofit with no experience in Oregon played a central role in shaping City Hall’s plan to open outdoor, city-run encampments for homeless Portlanders. The San Francisco shelter operator, called Urban Alchemy, has been in talks with Wheeler’s office since April on bringing their model of outdoor encampments to Portland.

Urban Alchemy began in 2018 as a program offering mobile hygiene services and job assistance to unhoused people in San Francisco. The organization, which focuses on offering jobs to people exiting the criminal justice system, took off in early 2020, when Urban Alchemy was selected to run San Francisco’s first outdoor homeless encampment in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The nonprofit went on to oversee several more outdoor camps in San Francisco, before expanding to Los Angeles in December 2020. In 2021, San Francisco hired Urban Alchemy to take on a slightly different task: patrolling areas of the city with high concentrations of homeless camps and offering resources to those living outside. Urban Alchemy staff were contracted to do similar work in Los Angeles last year.

Notably, the organization has been granted several no-bid contracts worth tens of millions of dollars to oversee camps in San Francisco. In July 2022, Austin City Council selected Urban Alchemy to run an emergency overnight shelter in a rushed vote, where Urban Alchemy was the only contractor considered.

The nonprofit’s budget has grown 500 percent in under two years—and it has no intention of slowing down. According to an Urban Alchemy pamphlet shared with Wheeler’s office, the organization hopes to add three new urban areas to its portfolio by June 2025.

Wheeler first mentioned Urban Alchemy in a late October press conference where he and Commissioner Ryan first unveiled their proposal to ban street camping and create large outdoor encampments to hold homeless Portlanders. He said that city staffers were planning to visit Los Angeles the following week to tour encampments run by Urban Alchemy.

“We are in communication with national service providers that are used to operating at this scale,” said Wheeler. “Our local service providers are outstanding, but they haven't done programs like this at scale.”

“Urban Alchemy… has done programs similar to this in other states,” Wheeler continued. “And they’re very interested in having conversations about where our interests might align.”

Yet this was far from the first time city staff were planning on meeting with the organization.

According to Skylar Brocker-Knapp, a policy advisor for Wheeler, she was first introduced to Urban Alchemy during a February work trip to San Francisco to observe the city’s “Healthy Streets Operations Center,” a city program tasked with clearing homeless encampments and connecting unsheltered people to social services.

“The [city staff] told us that a big key to their success was this service provider, Urban Alchemy,” said Brocker-Knapp. “So we visited one of their sites, and were super impressed.”

After that visit, Brocker-Knapp asked San Francisco staff to introduce her office to Urban Alchemy leadership.

Emails obtained in a public records request show that city staff first connected with Urban Alchemy in April to discuss the organizations’ work. In June, staff in Wheeler’s office welcomed three members of Urban Alchemy’s leadership, including CEO Lena Miller, to meet in City Hall. Urban Alchemy employees again visited Portland to meet with Wheeler’s staff in early August.

By September, Urban Alchemy‘s “Chief Growth Officer” Jeff Kositsky had sent a detailed proposal to the mayor’s office for a “safe sleeping village” located in Portland. The proposal appeared to be a precursor to the city’s proposal, suggesting camps with up to 225 people, a staff ratio of one for every 15 campers, and a daily plan to serve two meals and one snack. These details were all included in the city’s initial proposal. No local nonprofits were sought out to provide similar proposals to City Hall at the time.

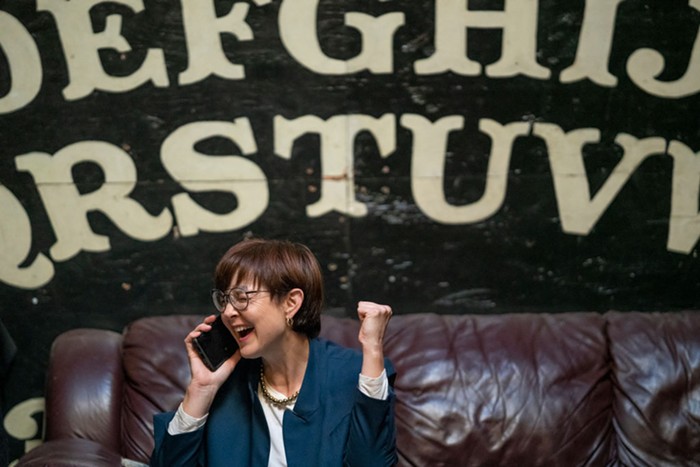

Urban Alchemy appeared to have secured a tentative deal with the city before Wheeler and Ryan even first unveiled the proposed camps. On October 17, Brocker-Knapp wrote an email introducing Urban Alchemy staff to Central City Concern CEO Andy Mendenhall, noting that she wanted the two organizations to connect since the city is “partner”-ing with Urban Alchemy. In describing Urban Alchemy, Brocker-Knapp wrote: “They are incredible people doing incredible work and we are so excited to bring them to Portland.”

"Urban Alchemy has a great model. But the [city's encampment] idea was an amalgamation of several programs."

On October 21, Wheeler and Ryan announced the encampment plan, paired with a strategy to ban street camping by 2024. Brocker-Knapp said the city's plan wasn't single-handedly informed by Urban Alchemy's proposal, but also reflected ideas gleaned from city-run homeless encampments in Vancouver, Denver, Austin, and other municipalities.

“Urban Alchemy has a great model,” Brocker-Knapp told the Mercury. “But the idea was an amalgamation of several programs.”

A week after the city’s announcement, Urban Alchemy’s Kositsky gave the mayor’s office an update on their partnership with the city, appearing to imply that the organization was part of the city’s camp proposal.

“It is very exciting that things seem to be moving forward!” wrote Kositsky, who explained that he was taking the lead in “managing our possible move to Portland.” Kositsky also proposed holding ongoing weekly meetings with city staff.

Despite the tone of these emails, Brocker-Knapp says that there is “no guarantee” that Urban Alchemy will be operating any of the Portland encampments.

“No contract has been signed,” she said. “There are multiple groups interested in overseeing the sites."

The city will open up a competitive bidding process on the contract to operate the camps in the next several weeks. According to Brocker-Knapp, the city isn’t asking prospective contractors to bid on a certain number of encampments, but simply submit a proposal to operate “alternative shelter sites” more generally. The contracts will likely be awarded in January.

Urban Alchemy will certainly be vying for that contract. In an interview with the Mercury, Urban Alchemy's chief of government and community affairs Kirkpatrick Tyler said that the nonprofit is excited at the opportunity to bring their expertise to Portland.

Tyler, who has visited Portland twice for work this year, said that there's something unique about the way the city addresses its homeless crisis.

"What I enjoyed about Portland is that there’s a genuine desire for everyone to come to a solution on the issue," said Tyler. "Sometimes, in other markets, we see folks take disagreement on a solution personally. In Portland, people appear to be okay with having different points of view, as long as they all agree that everybody is trying to do their best."

Tyler said he is also impressed with the thoughtfulness in which Portland evaluate potential locations for an outdoor camp.

"In Portland, people appear to be okay with having different points of view, as long as they all agree that everybody is trying to do their best."

Local service providers who may compete against Urban Alchemy to oversee an encampment are still uncertain if the city's general plan—inspired by out–of-state organizations—will fit Portland’s unique needs.

Juliana Lukasik, a spokesperson for Central City Concern (CCC), said that her organization remains concerned about the structural uncertainty of the camps. The nonprofit's biggest worry centers on staffing. Oregon is currently facing a shortage of nearly 35,000 behavioral health care workers, according to a report released in September by PSU and OHSU’s School of Public Health.

Without a promise from the federal or state government to help expand that workforce, Lukasik doesn’t see how the city’s encampments will be able to adequately address the mental health needs of its residents.

“That’s what I lose sleep over,” she said. “That we’ll offer people the ability to be safer at night than they were previously and maybe some hygiene services, but that we won’t have anyone to genuinely help them move forward or have anywhere to send them. We call that ‘navigation to nowhere.’ A shelter can only work if we’re moving people out of it.”

Lukasik and CCC CEO Mendenhall met with Urban Alchemy staff once virtually, and said the conversation left them with more questions than answers about how a large-scale camp could operate.

"That’s what I lose sleep over. That we’ll offer people the ability to be safer at night than they were previously and maybe some hygiene services, but that we won’t have anyone to genuinely help them move forward or have anywhere to send them."

Urban Alchemy's Tyler doesn't consider his organization operating as competition to local Portland service providers. If awarded the encampment contract, Tyler said, Urban Alchemy will work to "fill gaps" in current service offerings. Because Urban Alchemy specifically seeks to hires people exiting long-term incarceration, Tyler said the nonprofit's presence shouldn't cut into the local homeless service provider labor pool.

While he admits that Urban Alchemy staff can't replace mental health workers, Tyler doesn't consider the state shortage in behavioral health workers a major hurdle for the organization.

"Our teams are able to create safe sustainable environments for hard-to-serve residents, which reduces the need for aggressive mental health support," said Tyler. "We've observed that when people enter a stabilized environment where people are supporting them where they aren't worried about being moved or victimized... that has cut that need [for mental health care] in half."

Several other local homeless service providers have been introduced to Urban Alchemy leadership through the mayor’s office.

Andy Goebel, director of All Good Northwest, a nonprofit that runs several of the city’s Safe Rest Villages, also spoke with Urban Alchemy staff in late October. Goebel said All Good has no interest in operating the new outdoor encampments, but hoped his perspective on running an outdoor shelter in Portland helped Urban Alchemy understand what they may be dealing with, in terms of climate, workforce stressors, infrastructure needs, and so on.

“My goal… was to get to know this organization, to learn more about their service provision modalities, and if helpful, to offer to think through some of those realities,” said Goebel.

Miller, of Our Just Future, said he was brought in on a virtual meeting with Urban Alchemy through the mayor’s office after the city announced its encampment plan—and after he publicly spoke out against the idea.

“It was an opportunity to talk about what's happening in the provider community in Portland,” said Miller. “And to let them know that, because several providers are not supportive of the proposal, that they might be coming in to staff something that there’s significant opposition to.”

"We've observed that when people enter a stabilized environment where people are supporting them where they aren't worried about being moved or victimized... that has cut that need [for mental health care] in half."

Miller believes the city intentionally sought input from homeless providers outside of the state, because Portland providers didn’t agree with Wheeler and Ryan’s approach to addressing homelessness. This theory was underscored for Miller last Thursday, when Wheeler chastised local homeless service leaders in a panel discussion with Portland business leaders.

“I have these so-called experts telling me I’m inhumane…. Because I’m asking people not to occupy our public spaces wall to wall,” Wheeler told the audience gathered at the downtown Hilton. “At some point for me I’ll take common sense over expertise.”

Urban Alchemy’s approach is notably different from nonprofits operating in Portland.

The organization’s patrol teams routinely partner with local law enforcement to help enforce homeless campsite sweeps, and often work as security guards at encampments, despite not obtaining a state private security license to do so. The company has also been accused of falling short on a promise to offer living wages to its staff—most who’ve experienced homelessness or incarceration—and creating an unsafe work environment.

This record has turned some homeless advocacy groups against the fast-growing nonprofit, and attracted litigation. Urban Alchemy has been sued by an employee alleging sexual harassment by a coworker and two additional lawsuits accusing the organization of not paying for overtime and breaks. Three homeless individuals have also sued the organization for civil rights violations by Urban Alchemy employees.

Tyler knows Urban Alchemy will face critique if it moves to Portland, as it has in other cities.

"It’s such a big lift," he said. "We are directing resources into something that folks aren’t always sure of, we are engaging in communities who may be used to looking at the issue from a different perspective. Us being vulnerable and transparent has helped us overcome that in other communities."