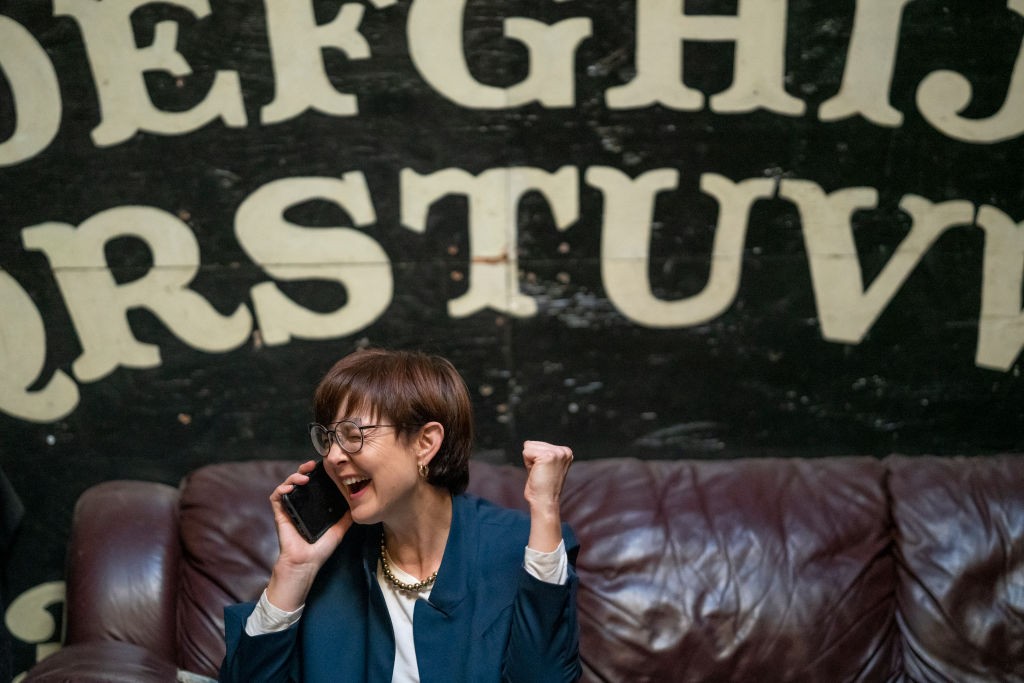

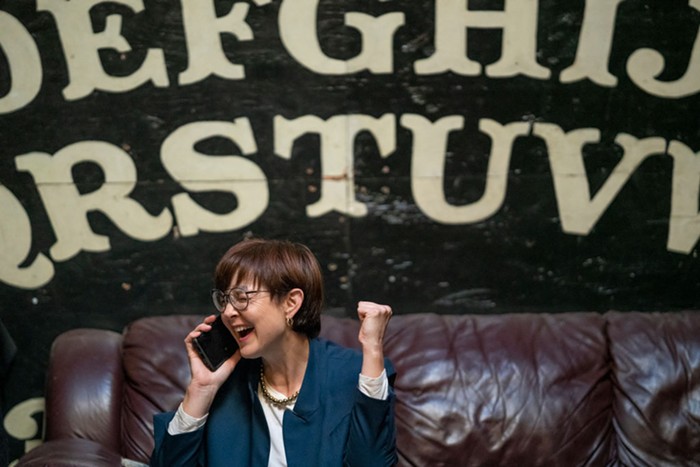

When former mayoral candidate Sarah Iannarone launched her second campaign in 2019, she still had plenty to learn about being a major candidate for public office. Some of the lessons were predictable. Others were not.

“One of the first things that someone taught me when I was running for office was how to get fitted for a proper bra,” Iannarone said. “I didn’t even know that that was a thing.”

Judith Rizzio joined Iannarone’s campaign as a “style activist” that year, and one of her first directives in the role was to send the candidate to The Pencil Test, a boutique then located on NE Alberta St., with an assignment: buy two bras that fit.

The focus on Iannarone’s style didn’t stop there. Rizzio said that during the course of the campaign, which Iannarone ultimately lost to incumbent Mayor Ted Wheeler, the pair scrutinized everything from Iannarone’s glasses to the collars on her shirts to the size of her earrings.

“Wherever you are as a candidate, you are being looked at,” Rizzio said.

It’s that kind of knowledge that Iannarone and her team with Our Portland, a political action committee, are hoping to impart by launching a Candidate School for prospective candidates and campaign workers in preparation for a major election season ahead of the expansion of Portland City Council in 2025.

The school, set to be held at the Self Enhancement Inc. building in July, will teach candidate and campaign workers about the nuts and bolts of building a campaign staff, talking to media, and, of course, the importance of a campaign wardrobe. The school will run over the course of a week, with between 50 and 100 participants in each program.

There will be a heavy focus on public policy, too—Greg McKelvey, who managed Iannarone’s 2020 campaign and helps run Our Portland, said the school will devote a day-and-a-half to policy matters—but for candidates like Iannarone, that might not be what’s most impactful.

“It’s what I learned apart from the policies that really matters, like how to connect with people, how to phone bank and dial for dollars, how to dress, how to act on camera, how to talk to the media,” Iannarone said. “These are things that [with] no amount of policy expertise would I have known.”

Rizzio is slated to be a speaker at the candidate school, where Iannarone said she’ll be “teaching people how to dress if you’re not born to wear a business suit.” Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt, former Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury, and former Portland Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty are also among the expected speakers at the school.

Iannarone said that the idea for the school is based in large part on the long-running Oregon Labor Candidate School, a program run by a coalition of labor organizations that helps train labor leaders for political office. Iannarone said she participated in the labor school's one-day training when she ran for mayor. The political arm of The Street Trust, where Iannarone serves as executive director, has a transportation candidate school.

But Our Portland occupies a particular position in the Portland political landscape: formed after Iannarone lost her 2020 bid for mayor, the PAC is broadly dedicated to advancing progressive goals and candidacies in the city instead of organizing around specific issues.

The Candidate School will be held just over a year before an election that has the potential to completely reshape city politics. The charter reform measure passed by voters last year will expand the council from four positions to twelve, with council members elected from four geographic districts rather than by all voters in the city.

Every current city commissioner plus the mayor will be up for election—giving Portland progressives, who have despaired as the city council has become more conservative over the last two election cycles, an opportunity to reclaim power.

“Charter reform happening is really the main catalyst for why we want to do it now,” McKelvey said. “With all these new seats, we're going to need quality candidates in each district.”

Our Portland already has a significant reach. McKelvey said the PAC’s email list, carried over from Iannarone’s mayoral run, includes more than 10,000 addresses and that its emails are opened by 50 percent of their recipients—unusually high numbers for progressive Portland politics.

McKelvey said he anticipates the PAC will endorse candidates and use the mailing list to raise money for them in 2024, giving progressives, he hopes, an opportunity to close the kind of money gap that Iannarone and Hardesty dealt with in their races against more conservative candidates.

That kind of coordination may prove key in a 2024 campaign that will feature a record number of city council races and, likely, a high number of first-time candidates.

“When you look at who has historically had access to power in this city, and who maintains quite a strong hold on it today, those people have strong networks both internal and external,” Iannarone said. “They’re connected to people who can write checks, they’re connected to institutional power and individual power, and they’re connected to each other because they’ve been doing this a very long time.”

Iannarone pointed to the campaign that coalesced to oppose charter reform, comprised of a number of current and former city council members and business leaders, as an example of the level of organization progressives are facing.

“The more conservative elements close ranks really quickly and fast, mostly in opposition to people, but also in support of people as well,” McKelvey said. “Progressives have not done that with the same efficiency.”

One of the biggest goals of the school is simply to get progressives on the same page and introduce potential candidates and staffers to each other, helping them begin to form the kinds of networks that they will be able to rely on if they decide to run next year.

They also want to be honest with would-be candidates about the often grueling nature of running for office, especially for candidates of color and candidates who are not cisgender men. Iannarone said that had she known all that being a candidate entailed, she might not have run—and that strong support systems are critical for people who do decide to step forward.

“It would have been nice to have other people with whom I could talk and connect so I didn’t feel so isolated, because that’s really hard,” she said.

But McKelvey said that despite the demoralization many in the progressive movement are feeling, interest in the candidate school has been beyond what he expected—motivated, in part, by the opportunities around the corner.

Iannarone sees that kind of excitement and interest in organizing as a potential roadmap for the city’s progressive movement to get its electoral groove back.

“The business class that wanted to get leadership has not effectively led during their time in power,” Iannarone said. “So what's really going to get us back in the game is when we get progressive win after win and we start to change what life is like in our city.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified the leader of the Oregon Labor Candidate School (OLCS) as SEIU. OLCS is run by a coalition of labor groups, including SEIU, AFSCME, ONA, and more.