In late 2019, State Senator Michael Dembrow and his colleagues on the Senate Judiciary Committee met with a group of incarcerated Oregonians presenting research on issues affecting the state’s incarcerated population.

One of the proposals the group presented to legislators was potentially groundbreaking: restoring the right to vote to people imprisoned for felonies.

“I have to admit that my first response to it was, ‘Woah. That’s going to take some getting used to,’” Dembrow, who represents parts of Northeast and Southeast Portland, said.

Oregon currently restores voting rights to people who have been convicted of felonies after they are released from prison. After hearing the arguments presented during the meeting, it didn’t take Dembrow long to overcome his initial skepticism about going a step further.

“The worst thing to have happen is to have [adults in custody] who are treated as isolated from the real world,” Dembrow said. “You want them to be thinking about the issues that their families are facing, that their communities are facing. Voting is part of that.”

Three years later, Oregon has the opportunity to position itself at the vanguard of a nationwide movement to restore voting rights to incarcerated Americans. A coalition of progressive organizations and legislators are backing Senate Bill 579, which, if it passes the state legislature and is signed by Governor Tina Kotek, would allow people convicted of a felony to vote in prison. If passed, the bill would restore voting rights to about 12,000 people in Oregon.

The movement to restore voting rights to people who are incarcerated has been gathering steam for the past several years. It got national attention in 2019, when Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders became the only candidate for president to endorse the idea, calling voting rights for all citizens “a basic principle of democracy.”

Vermont and Maine are the only two states that have never stripped incarcerated people of their right to vote. People in prison cannot vote in any of the other 48 states, and no state—with the exception of Washington, DC—has ever restored the right to vote to people incarcerated for felonies. In some states, even people who have completed their sentences are still denied their right to vote. More than 4.5 million Americans are disenfranchised across the country.

But that could change this year. In addition to the push in Oregon, California and over a dozen other states are considering bills to extend voting rights to incarcerated people in their current legislative sessions.

Bills to restore voting rights to incarcerated people have been introduced in Oregon twice before in the 2021 and 2022 legislative sessions, but have failed to advance past the Joint Committee On Ways and Means.

Supporters of the 2022 bill cited unified Republican resistance and election year politics as reasons the effort failed, though Dembrow said he and his colleagues were told by the group they met in 2019 with that the state’s incarcerated prison population would likely have supported Donald Trump had they been able to vote in the last presidential election.

This year, however, the bill’s backers believe they have their best chance yet to pass it—arguing that legislators who were in office during the last two years have grown more comfortable with a bill that challenges conceptions about the purpose of incarceration.

If punishment is the aim, stripping people of their right to vote makes sense. But if the aim is community safety, the bill’s backers say, it is imperative to remember that the vast majority of people who are incarcerated in Oregon will eventually leave prison and rejoin their communities at home—and research shows that people who maintain familial and communal connections have an easier time when they get out of prison.

In Dembrow’s view, setting people up appropriately for that transition is in everyone’s interest. Voting rights can play a small part.

“If we are really serious about making our community safer, we need to find a way to bring down our recidivism,” Dembrow said. “Again, it is very clear that in countries with lower recidivism rates, they would never consider revoking the right to vote.”

According to Human Rights Watch, the United States—which has the world’s largest prison population and one of its highest recidivism rates—may also have its “most restrictive criminal disenfranchisement laws.” Disenfranchising citizens while they’re incarcerated is not a particularly common practice among other comparable nations. In France’s last presidential election, turnout among incarcerated people soared following dedicated efforts to improve ballot access in prisons.

The extent to which incarcerated people should be cut off from their membership in the community is a central question raised by the bill.

“It makes a statement… [that although] they are physically separated from much of their community, that doesn’t mean that they are disengaged or not impacted by what is happening in the state as a whole,” Alice Lundell, director of communication at the Oregon Justice Resource Center, said. “The recognition that this bill offers to that fact is really important to people.”

That assertion is backed by testimony incarcerated Oregonians offered on SB 579 in the Senate Judiciary Committee at the end of January.

“Years ago, I went completely out of my way to put myself on the “non-active” voter registry as an inmate,” Phillip Bates, who is incarcerated in Ontario, wrote in his testimony. “That is how much the principle means to me. To switch to becoming an active voter would mean the world to me. Allowing me to vote would tell me I am worth something.”

Voting rights for incarcerated citizens is also a racial justice issue. Black Oregonians are incarcerated at a rate nearly four times that of white Oregonians, with Latino and Indigenous people historically overrepresented in Oregon prisons as well.

Jessica Maravilla, policy director at the ACLU of Oregon, said that is no accident. The push to ban incarcerated people from voting arose alongside literacy tests and poll taxes after the Civil War when Black Americans were granted the right to vote.

“Voting exclusion based on incarceration comes from a history of anti-blackness and white supremacy,” Maravilla said. “It’s really an outdated Jim Crow law that is aimed at disenfranchising Black people, and today this law continues to disproportionately disenfranchise Black, Latinx, and Indigenous citizens. This is about reversing these outdated, anti-Black laws.”

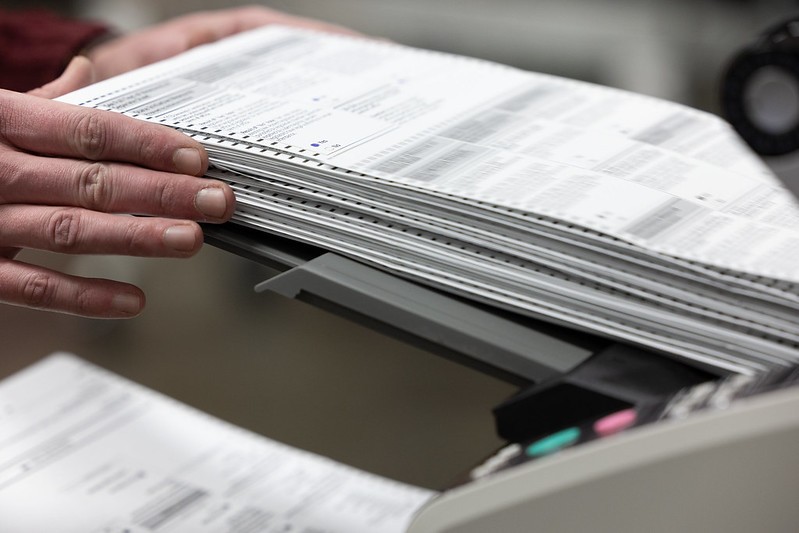

Logistically, Oregon is in a good position to restore voting rights to incarcerated people. Because the state already uses a vote-by-mail system, it would be fairly simple to get ballots and materials like voters’ pamphlets to incarcerated citizens.

If the bill passes, incarcerated Oregonians would be registered to vote based on where they lived prior to their period of incarceration. It’s unclear how many incarcerated people would exercise their right to vote, but data from Vermont and Maine suggests a lack of internet access, voter issue education, and literacy could still act as barriers to voting in prison.

But increasing voter participation is a long-term project that Oregon has committed itself to in other ways, like enacting a first-in-the-nation automatic voter registration law. For Maravilla, ensuring that every citizen has the right to vote would not only be in alignment with the state’s goal of increasing voter participation, but would also right a moral wrong.

“Ninety-five percent of incarcerated people will actually return to their communities,” Maravilla said. “Incarceration does not justify taking away their voice.”